Python-Blosc2 4.0: Unleashing Compute Speed with miniexpr

We are thrilled to announce the immediate availability of Python-Blosc2 4.0. This major release represents a significant architectural leap forward: we have given new powers to the internal compute engine by adding support for miniexpr, so it is possible now to evaluate expressions on blocks rather than chunks.

The result? Python-Blosc2 is now not just a fast storage library, but a compute powerhouse that can outperform specialized in-memory engines like NumPy or even NumExpr, even while handling compressed data.

Beating the Memory Wall (Again)

In our previous post, The Surprising Speed of Compressed Data: A Roofline Story, we showed how Blosc2 outruns the competition for out-of-core workloads, but for in-memory, low-intensity computations it often lagged behind Numexpr. Our faith in the compression-first Blosc2 paradigm, which is optimized for cache hierarchies, motivated the development of miniexpr. This is a purpose-built, thread-safe evaluator with vectorization capabilities, SIMD acceleration for common math functions and following NumPy conventions for type inference and promotions. We didn't just optimize existing code; we built a new engine from scratch to exploit modern CPU caches.

As a result, Python-Blosc2 4.0 improves greatly on earlier Blosc2 versions for memory-bound workloads:

- The new miniexpr path dramatically improves low-intensity performance in memory.

- The biggest gains are in the very-low/low kernels where cache traffic dominates.

- High-intensity (compute-bound) workloads remain essentially unchanged, as expected.

- Real-world applications like Cat2Cloud see immediate speedups (up to 4.5x) for data-intensive operations.

Keep reading to learn more about the results.

The Power of Block-Level Evaluation

In previous versions, Python-Blosc2 evaluated lazy expressions chunk-by-chunk. While efficient, we knew we could do better by making things more granular.

Version 4.0 introduces a deeper integration with miniexpr. A chunk is the unit of storage (typically MBs), while a block is the unit of compression (typically KBs, fitting in L1 cache). Instead of decompressing entire chunks (which might not fit in CPU caches, as they are composed of several blocks) and passing them on to be processed, the new engine works directly on compressed Blosc2 blocks—small, cache-friendly units of data that fit comfortably in L1/L2 caches. Once the blocks for operands have been decompressed, miniexpr uses its expression engine designed to keep the working set in L1/L2 as much as possible, and Blosc2 is in charge of coordinating the internal thread pool to process them in parallel.

This granular approach achieves two critical goals:

- Cache Locality: By keeping operands in the fastest CPU memory tiers during evaluation, we minimize costly RAM access.

- Compression Synergy: Compression and computation now happen in the same pass. The data is kept hot in the cache after decompression and immediately consumed by the expression engine.

Visualizing the Upgrade: From Computing with Chunks to Blocks

To help visualize this internal revolution, we have created an animation comparing the workflow of the previous engine with the new miniexpr-based one.

As seen above, the miniexpr workflow simplifies the path data takes from storage to result. It eliminates the overhead of hosting large chunks in memory, which typically spill into L3/RAM and cause slowdowns. With miniexpr, operands are processed in blocks, which fit comfortably in L1/L2 caches.

Why miniexpr?

Until now, Python-Blosc2 has used a combination of NumPy and Numexpr for evaluating expressions on compressed data. However, it is challenging to use these packages efficiently in multithreaded applications. miniexpr is a new vectorized pure-C expression engine that is thread-safe and can be used in multi-threaded applications. We leverage the prefilter mechanism in Blosc2 to implement the miniexpr computation engine - allowing us to perform computations on compressed data transparently and very efficiently.

In addition to vectorization, miniexpr can use modern SIMD instructions in modern hardware (like AVX2 in AMD64, or NEON for ARM) via SLEEF to accelerate transcendental functions and other math kernels - improving performance even further for functions like sin, cos, exp, etc. Finally, miniexpr has a small memory footprint, which is important for performance on memory-constrained devices like Raspberry Pi.

Before/After: A Quick Look

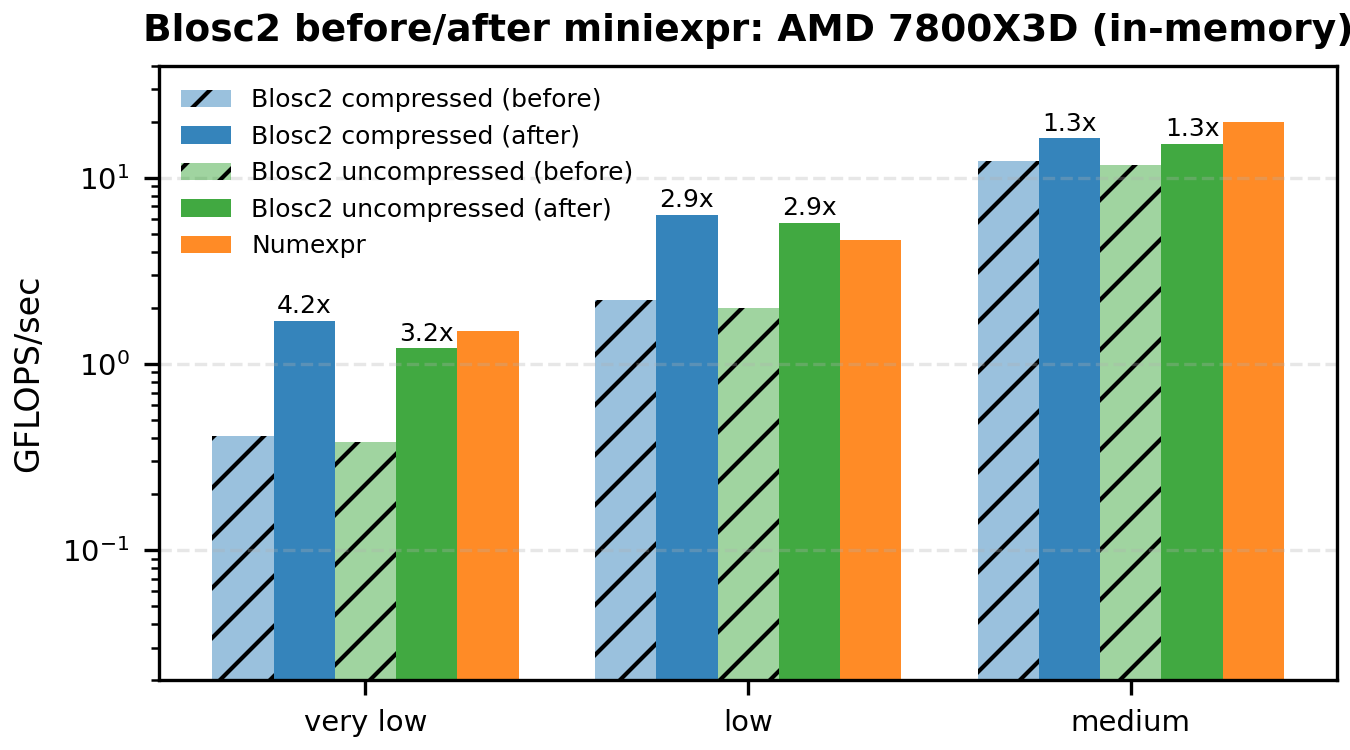

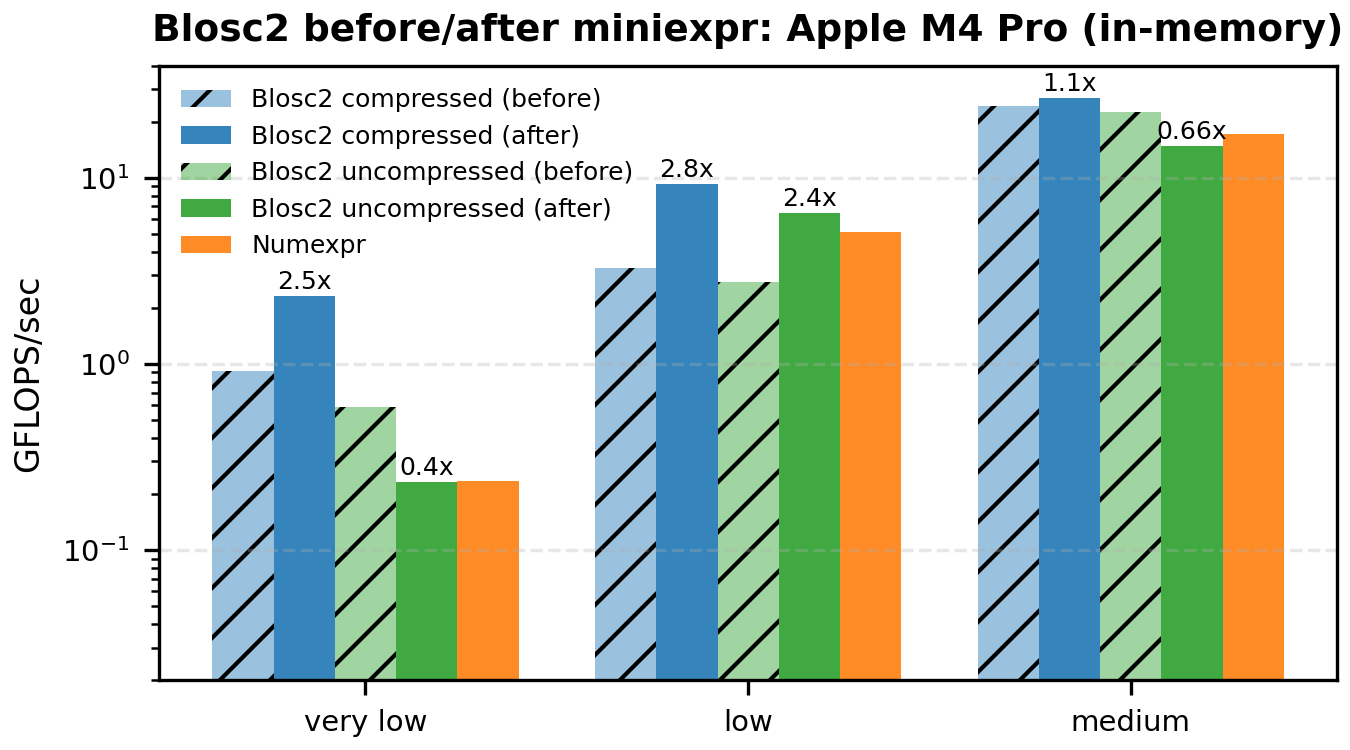

The following bar plots compare the original vs miniexpr-based compute engines for Blosc2 (both for compressed and uncompressed workloads). We show only the low-to-medium intensities – where the memory wall dominates and the changes are most visible.

For in-memory workloads:

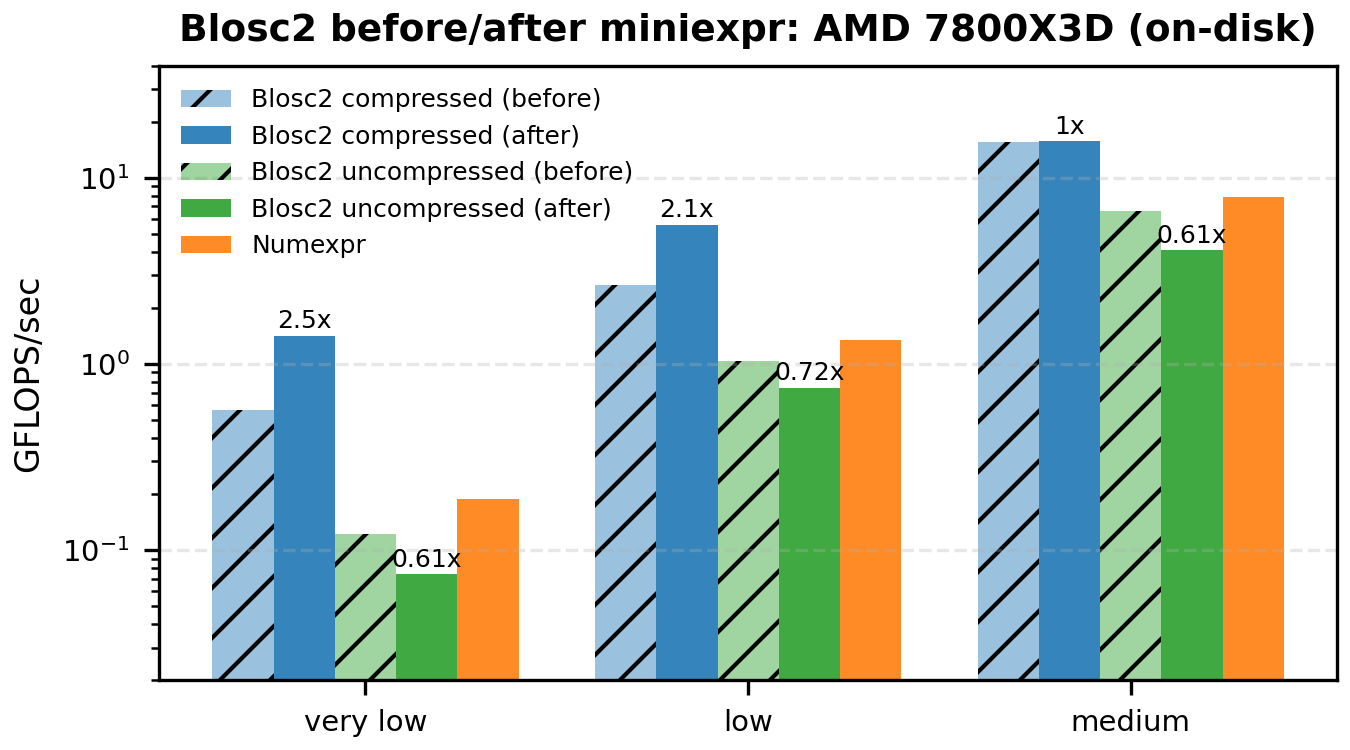

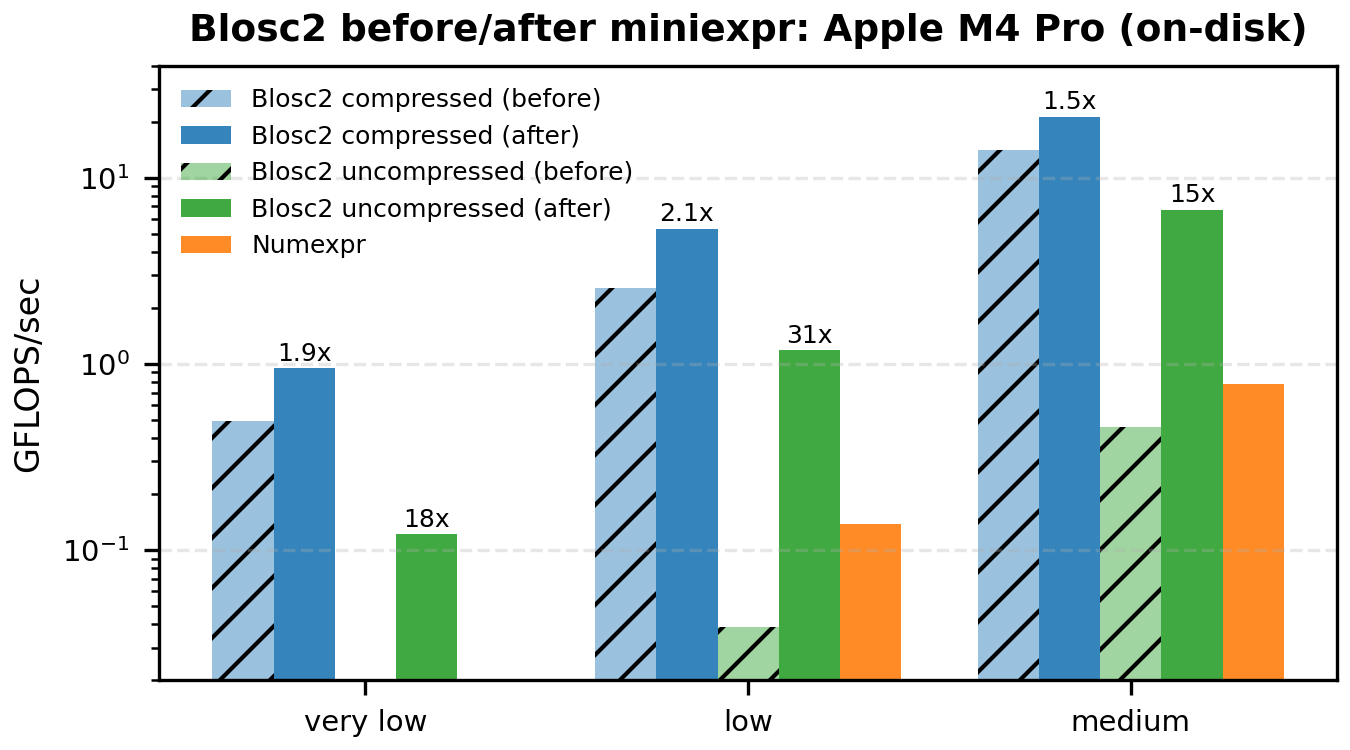

And for on-disk workloads:

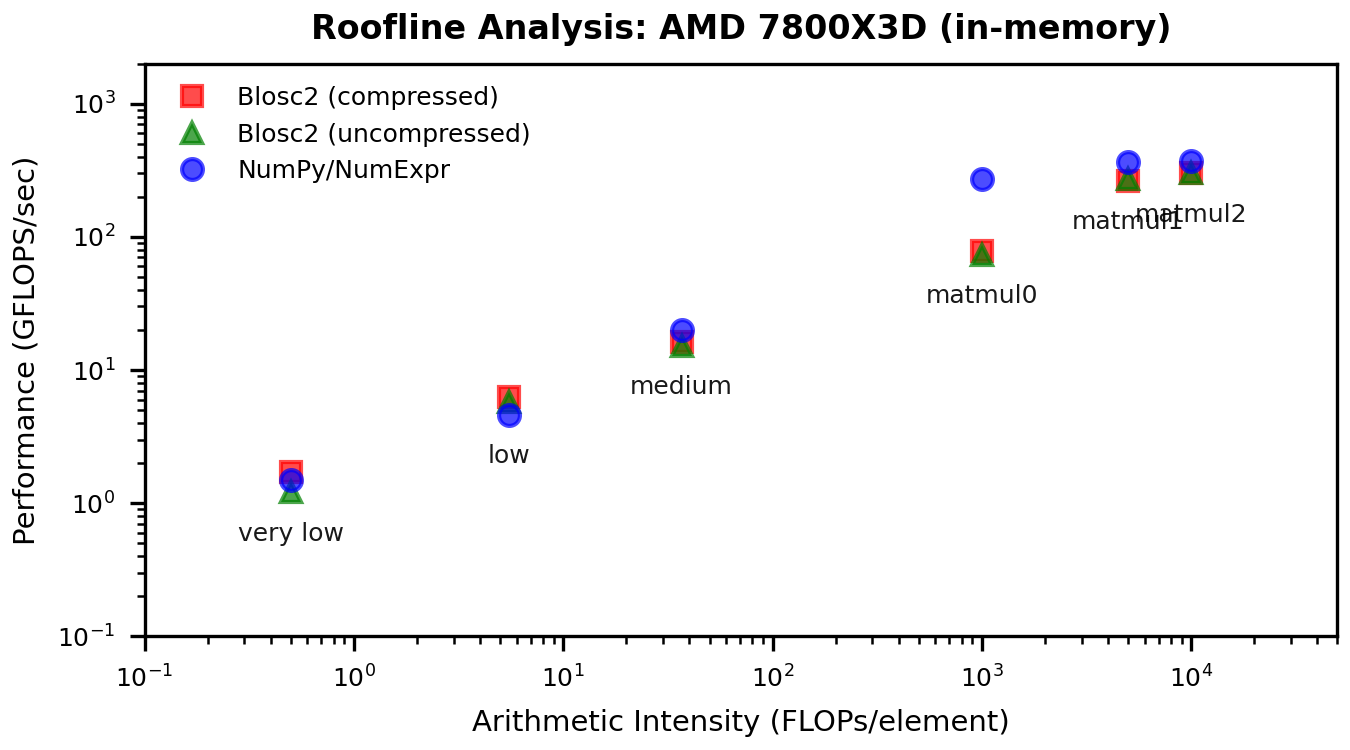

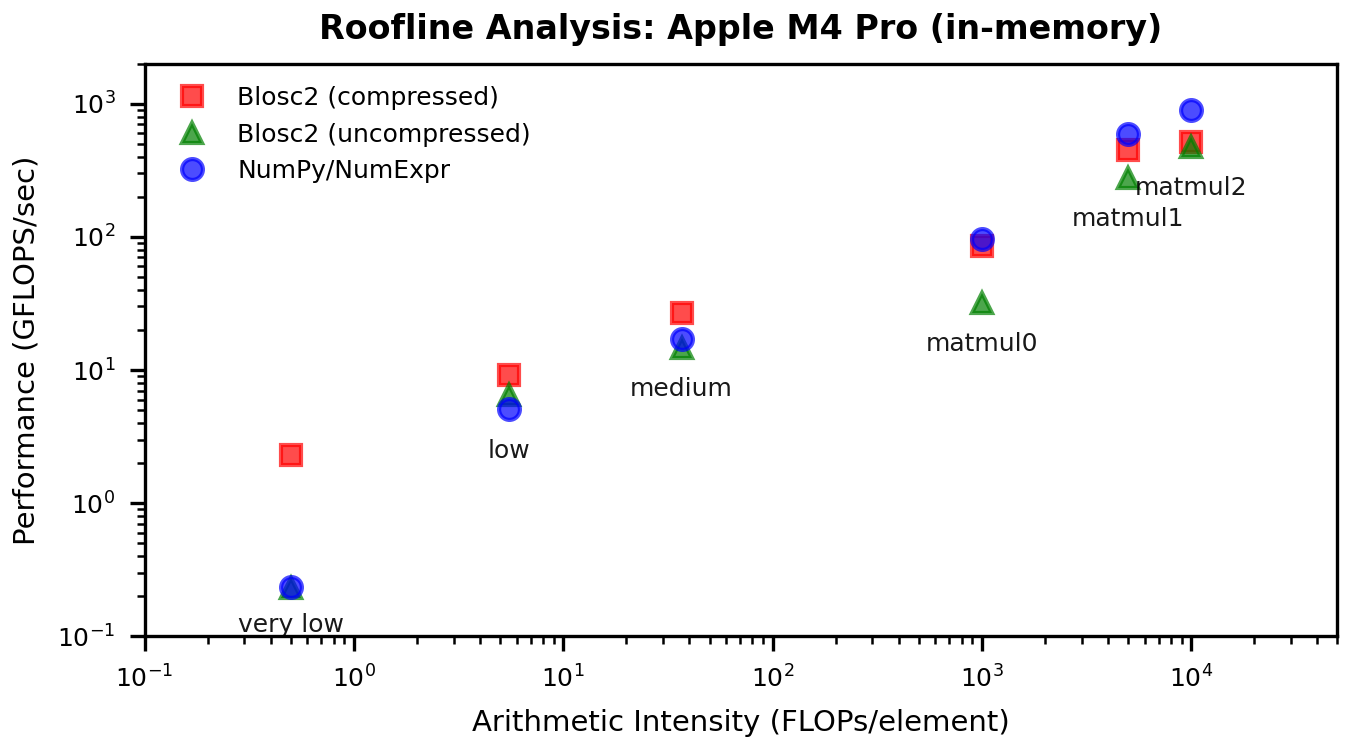

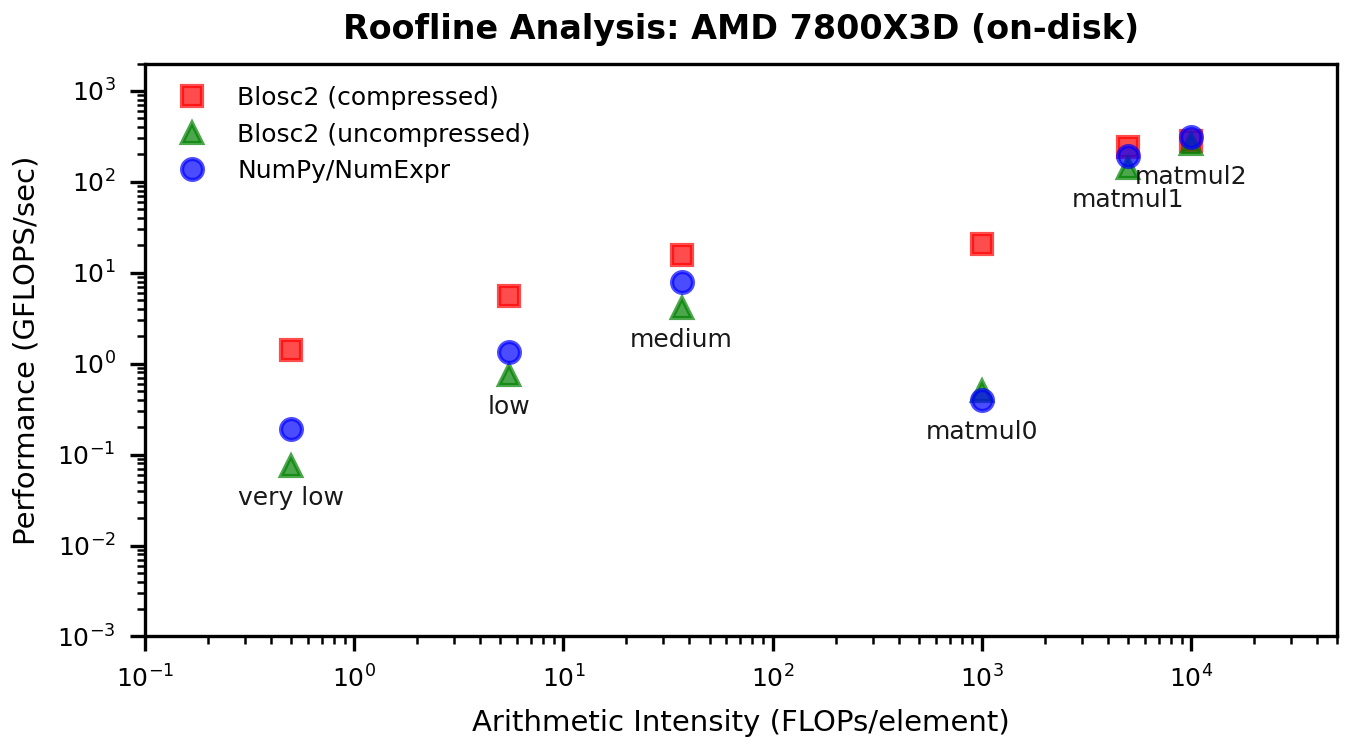

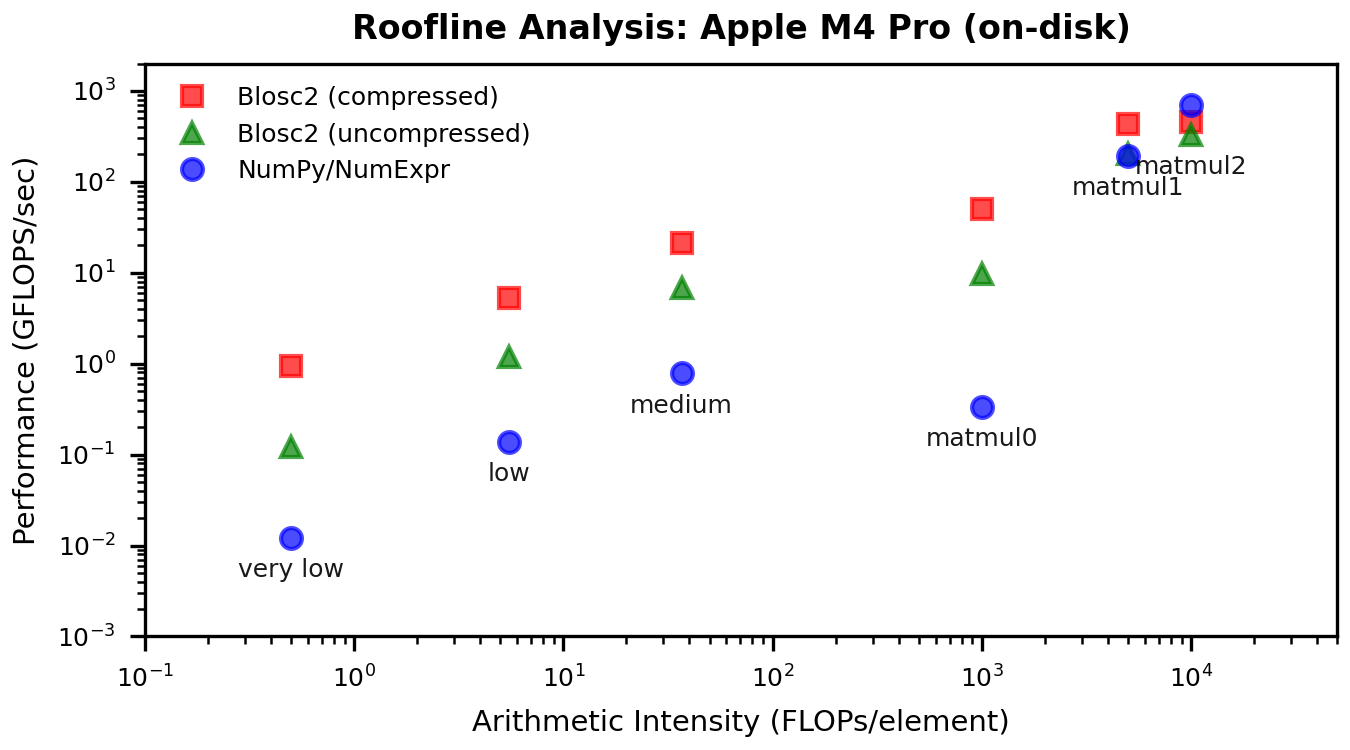

Roofline Context

To connect these performance gains to the memory wall, here are updated roofline plots. These show how the low-intensity points move up (i.e. increased computation speed) without changing arithmetic intensity — exactly what we expect when cache traffic is reduced.

Results for in-memory workloads:

Results for on-disk workloads:

Discussion: What Changed?

The miniexpr engine speeds up computation in low-intensity cases due to reduced cache traffic and indexing costs, which mean the engine is able to feed data to the processor faster. High-intensity operations (which are compute-bound, and so not limited by data transfer) are neither faster nor slower, as expected.

Here there are worth noting two key differences between the previous path and miniexpr:

-

Caching: The previous path evaluated whole chunks per operand, which inflated the working set beyond L2/L1 and pushed a lot of data into L3 and even memory. With miniexpr, computation happens on (small) blocks in parallel, keeping most traffic in L1/L2 and shrinking the working set per thread.

-

Indexing: Due to its design paradigm, miniexpr fetches data from the full array (stored in memory, disk or network) more rapidly and distributes it directly to computation threads, saving on overheads present for the previous path.

Note that the miniexpr engine only functions on operands which are aligned — meaning they share the same chunk and block shapes, which is typical for large arrays with consistent layouts. If operands are not aligned, Python-Blosc2 simply calls the previous chunk/numexpr engine, ensuring calculations may be performed for any array layout.

A note on baselines: on our Mac M4 box runs, the Numexpr in-memory baseline is lower than in the original post. We re-ran the benchmark several times, and the numbers are stable, but we did not pin down the exact cause (BLAS build or dataset/layout differences are plausible). The comparisons here are still apples-to-apples because all runs are from the same environment.

A Note on Regressions

There is one case where results regress: AMD on-disk, uncompressed. The most plausible explanation is a trade-off between sequential block access and chunk overlap. In the previous chunk/numexpr path, the next chunk could be read in parallel while worker threads were computing on the current one. In the miniexpr path, all blocks of a chunk must be read sequentially before the block-level compute phase starts, so that overlap is largely lost. This would disproportionately hurt the on-disk, uncompressed case on AMD/Linux.

The curious part is that, for the equivalent Apple M4 on-disk and uncompressed scenario, the miniexpr path actually improves performance, which suggests that parallel chunk reads were not helping much on MacOS (for reasons we do not yet understand). Although the uncompressed path is not really the most pressing worry for our users, we will keep investigating ways to mitigate this trade-off.

Impact in Cat2Cloud

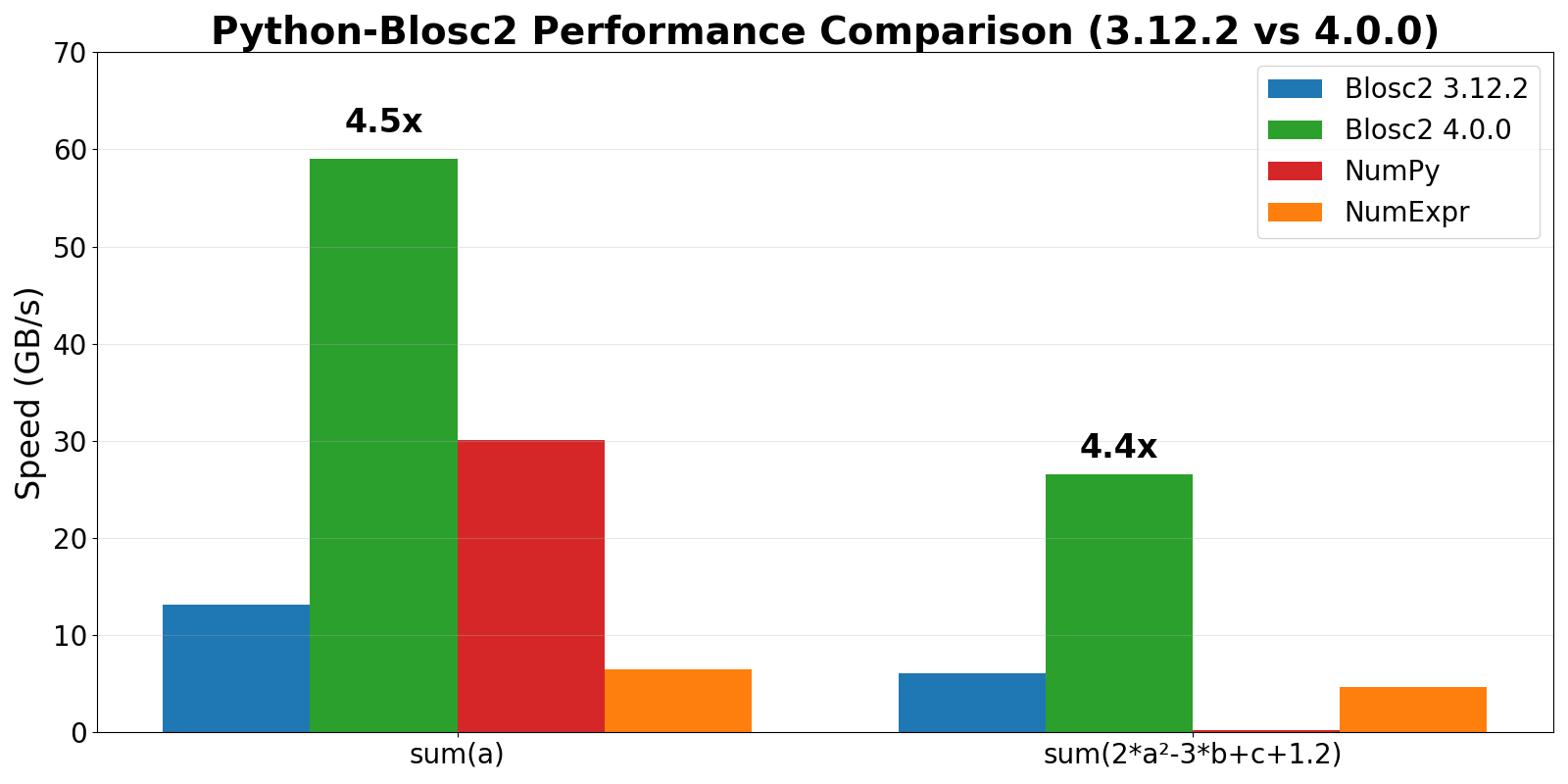

Cat2Cloud is our cloud-based data management platform that uses Python-Blosc2 for on-disk compression and computation. One of our main goals is to make it as fast as possible, and we are thrilled to see that miniexpr has helped us achieve this goal, as you can see in the following benchmarks:

As you can see, Python-Blosc2 4.0 is a big step forward for Cat2Cloud, increasing the speed of low-intensity computations (reductions in this case) by up to 4.5x. Note that this technology isn't just a theoretical benchmark—it is the engine running under the hood of Cat2Cloud right now. Queries that used to take seconds now happen in the blink of an eye, enabling true interactive exploration of massive datasets directly in the cloud.

What's Next?

The next step is to continue improving miniexpr, and be able to use it in more code paths. Right now miniexpr can only be used in the prefilter pipeline, and that means that only operands sharing the same chunk and block shapes can benefit from it. Also, Windows support is currently limited (e.g., expressions with different data types are not yet supported). It would be nice to find ways to overcome these limitations and make miniexpr more widely available inside Python-Blosc2.

Conclusion

miniexpr flips the "surprising story" from the previous post. In-memory, low-intensity kernels—the classic memory-wall case—now see large gains, while compute-bound workloads behave as expected. The roofline shifts confirm the diagnosis: this is a cache-traffic problem, and miniexpr fixes it by working at the block level.

This is a big step forward for "compute-on-compressed-data" in Python and a strong foundation for future work (including the remaining on-disk regression).

We encourage you to upgrade and test your workloads:

pip install python-blosc2 -U

We look forward to hearing your feedback on the Blosc GitHub discussions!